By Daniel Ross

In this TDN series, we curry lessons and wise counsel from veteran Californian figures who, like gold nuggets panned from the Tuolomne River in the High Sierras, have unearthed career riches on arguably the toughest circuit in the States.

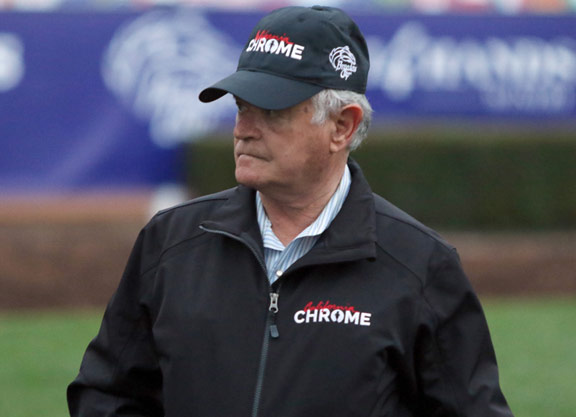

The series started with John Shirreffs and continues here with Art Sherman, son of a barber who would go on to train, for a period, the richest horse in history. Last month, Sherman announced his retirement. His last runner is expected this weekend.

The golf cart plunges out of the soupy early-morning fog swallowing Los Alamitos Racecourse like the focus of a slow-motion action sequence, Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries playing in the writer's ears, before rolling to a stop outside a barn with a plaque memorializing the GI Preakness S. of 2014.

Riding side-saddle on this mechanical rickshaw, Art Sherman springs from it like an elastic band–his 84 years be damned–marches over to a horse, all suds and statue–still on the wash rack, telling the groom and the hotwalker how well their soapy pupil had just schooled in the gates.

Commentary complete, Sherman finally heads for his office.

“That's it, I'm done for the morning,” he says. This, despite the clock hands reading 7:00, and the heavy foot traffic on the equine expressway leading to and from the track telling a far less finished story among the surrounding barns.

There are two reasons for the abbreviated workday–one is familiarity, a habit contracted from his former mentor, trainer Paul Guidotti.

“I'm always the first one on the racetrack. I just like to get my horses in and out and let them relax,” Sherman would later explain. “I don't like to wait for the horses to train and get tacked up and standing there and waiting.”

The other is practicality. With only a handful of horses in his care, the morning's a quick study.

Partly for this reason, Sherman has announced his retirement from training–though he won't disappear completely, looking to maintain an advisory role to his two trainer sons, Alan and Steve, and the occasional dabble in the world of bloodstock.

What the training ranks lose, however, is an important connecting thread between the sometimes sparse returns of California's current industry–short fields, disappearing farms, shrinking foal crops–with the profligacy of the industry's post-war extravagances.

None epitomize this more than owner-breeder Rex Ellsworth, who kept and raised hundreds of horses between farms in Ontario and Chino, inland from Los Angeles, and Sherman's first employer in racing.

“He grabbed my ass a couple of times and put me back in the saddle. I mean, I was airborne,” says Sherman, from his office chair, a hand shot airborne like a rocket as he describes Ellsworth's hands-on approach to breaking his young-stock, the old cowboy accompanying the crew on his pony-terrorizing them, too.

“He'd slap them under the belly. Boom!” he adds, another arm pretzel in the shape of Buckaroo.

For a period in the 1950s and the 1960s, Ellsworth and his trainer, Meshach Tenney, reigned supreme in the West–kings of an empire forged from California's golden sandy loam. But theirs was hardly a show-room operation.

Instead of sturdy white-picket fences, think barbed-wire. Instead of gourmet treats, think dry pellets manufactured on the ranch.

“I can't ever remember being with Rex and having any vitamins,” he says. “But all the horses looked good.”

Tenney shared that same spartan mentality. “He worked his ass off all day long. I used to hold the horses for him and he'd be shoeing them all afternoon, six or seven at a time.”

As for the horses, “They hardly were ever done up. I just used to feed them, no bandages.”

The Ellsworth school of rough-and-ready brooked no favor. “He broke every horse like he didn't care how they were bred,” says Sherman. Egalitarian, certainly. Uncompromising, too.

“You loved to ride their horses because when you rode them in the afternoon, they were broke,” he says. “They had to behave themselves, you know what I mean? This was a no-nonsense type of thing. There was no babying and feeding them sugar and all that.”

Spare the rod and spoil the child–back then, a backbone of a generational approach to raising horse and human alike.

In his own training career, however, Sherman has cultivated the opposite reputation.

Few who followed California Chrome's exploits could have failed to notice the rather doting paternal attention–akin to the proud father of the cocky jock–with which Sherman ushered the colt around the globe.

It's this careful approach that Sherman has used to produce a list of top performers nurtured over more seasons, and campaigned with much more of a competitive appetite, than is now standard.

“It's that confidence you build up between a horse and yourself, that you know you're doing the right thing and having a good rider ride them,” he says, in explanation. “That's very important, knowing your horse. I don't know how to even explain it.”

He doesn't need to explain it–it's right there in the numbers and the records. You have to go all the way back to 1991 to find the most recent winner of the GI Kentucky Derby, Strike the Gold, who raced more times than California Chrome. (The gelding Funny Cide, who won the 2003 Derby, isn't really a fair comparison).

Lykatill Hil, another of Sherman's multiple graded-stakes winning Faberge eggs, started his career two months before Bill Clinton won his first presidential election, and retired 19 wins from 61 starts later, only a few months short of that millennium's end.

Integral to Sherman's success, he says, was his own broad-brush grounding after he turned up on Ellsworth's doorstep without any practical experience with horses, and plunged straight into the breeding operation.

“He taught me everything and it wasn't the money,” he says, of his time with Ellsworth.

At the time, Khaled, sire of Swaps, was kingpin of the Ellsworth empire.

“I used to exercise him and keep him fit around the big pen. It was pretty interesting for a kid that never had been around horses,” says Sherman, bemoaning the lack of comparable opportunities for today's new racetrack inductees. “There are so many kids that have never been there around the breeding season, watching mares foal. Those things. They come to the racetrack now and want to be a jockey in a year's time, you know? But I think that schooling, the background of being at the ranch and working there for a year, really improved my mind about how a horse should be.”

His 22 years as a jockey proved something of a training manual pick-and-mix. “I think that helped a whole lot, getting the basics and watching different people train horses, you know what I mean? What works. Some of it doesn't work for a lot of people. I saw good horsemen-horsemen good with legs-but who could never condition a horse that great.”

But when asked who–or what–has been most influential in shaping his approach to training, Sherman steers straight towards Guidotti, who maintained a small stable in Northern California.

“You know, when I first started training I just decided I would just mostly be like Paul taking care of horses,” he says. “They always looked good. He was a good caretaker, good feed, top notch feed, you know what I mean? He gave vitamins which I do.”

Like Sherman now, Guidotti wasn't one for the morning bullets. “I'm not really for the fast workouts. I like distance. I like endurance. I like them to finish the last eighth of a mile and kick it in.”

Moral lessons were also on offer. “He's the only guy I ever seen fire an owner over me. They wanted to take me off a horse that I won a little stake on and then the horse got beat. He told them, 'If you change riders, just take him to another trainer.'”

Unlike Sherman, the horse found lodgings anew.

Home in Sherman's early years with a license consisted of the barn tack room, his wardrobe a bunch of cast-offs from a jockey who quit the saddle to become a Mormon missionary.

“I had a hotplate and a little small fridge. I liked staying in the tack rooms. It was fun. I had the old locker where I had my clothes.”

Some 40 years later, he retires the trainer of 2,261 winners and the fourth-highest earning horse in history.

Gone are the penitential digs.

“I just sold my place here. I had a condo here in Cypress,” he says, of his home near Los Alamitos. “I've got another place in Rancho Bernardo in San Diego.”

But acquired along the way has been one valuable lesson. “Patience is a lot of it, you know what I mean?” he says.

“You just can't, like I said, train every horse the same way. Some horses have got little quirks about them. You just got to realize what capabilities that your horse has. Conditions help you win races. Don't run them over their head. Don't put them in spots where they got to run their eyeballs out and get beat, you know what I mean? Don't over race them to a point where you take the heart out of them.”

In part two next week, Sherman talks Swaps and California Chrome, and gives his thoughts on the evolving shape of the California industry.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.